Through a provocative 20-year exploration of the iconographic power of the Confederate flag in The Recoloration Proclamation, John Sims has seemingly staked out his legacy in his own time. His work has shown in galleries across the country and been the topic of conversation in the national press.

But even these heights represent only a fraction of the artist's activity, coordinate points in a greater body of work defined more by repeated action and ritual than any one exhibition or art object. A magnum opus pieced together in the secrecy of plain sight and that seeks to become more than the sum of its many, many parts.

To see what has been built requires seeing the world as John Sims does—as a multitude of systems and endless cycles obeying unknowable laws in the throes of endless and unpredictable stimuli. The human experience, at both the individual and community level, emerges from the precarious balance of an ever-changing confluence of concerns, needs and myriad foci all hurtling through the national consciousness in “chaotic orbits” that appear and recede, overlap and amplify, obscure and engulf in a massive “geometry of conflict” that defines the fluidity of cultural existence. Sims doesn’t pretend to understand all of the complexities of these systems or hold any particular predictive talent, but he cannot ignore the possibility of what one could accomplish if they figured out how to affect even just one system in the right way. To offset that balance to a new equilibrium. With the right tool at the right time, could one man change the world?

“Small perturbations can create gigantic outcomes,” Sim booms with an audible grin. “And my work hovers around the places that are ready to explode.”

Shock the System and Hang the Confederacy

Granted, sometimes Sims lights the match himself, such as when he kicked off The Recoloration Proclamation in 2001 in the face of a KKK rally in St. Petersburg, handing out his own recolored Confederate flag bumper stickers to counterprotesters, Old Dixie reimagined in the red, black and green of the Black Liberation flag. Or when he followed it up with an exhibition in Harlem in 2002, advertising the show by draping a big honking orange and green Confederate flag out front. On both occasions, Sims found himself confronted by anger, first by a protester who saw Sims’s bumper stickers as “bastardizing the sacred colors” of the Pan-African flag and then by a black Harlemite who didn’t take kindly to a Confederate flag in his neighborhood, regardless of its colors.

(The former nearly came to blows, but Sims simply recorded both confrontations for inclusion in an experimental film to be released as soon as the project reaches its 20-year conclusion. Other highlights include a Civil War sci-fi narrative about gay marriage, racism and time traveling, featuring a bit part by ’70s-porn-star-turned-performance-artist Annie Sprinkle, the San Francisco icon.)

And sometimes Sims admittedly tosses a blazing torch into the powder magazine of white supremacy itself, such as 2004’s The Proper Way to Hang a Confederate Flag, an outdoor installation that called for the Confederate flag to be publicly hanged from a 13-foot gallows and displayed for three weeks at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania. Local papers called it a lynching. Sims called it apropos. “I’m hunting down your symbols and bringing them to justice,” he says, “like you were coming through my community looking for black men to hang.” Cue the death threats. Cue the phone calls with the FBI. Cue the college folding and reducing the exhibition from a three-week outdoor affair with a full gallows to a brief appearance in the corner of an indoor gallery sans gallows. Sims boycotted.

The installation would show in various compromised iterations over the years, including a 2006 exhibition alongside Dread Scott’s iconic What is the proper way to display a U.S. flag? at Ringling College of Art & Design, the first institution to actually construct a gallows for the piece, but Sims’s full vision would not be realized until a 2017 exhibition at the Kennedy Museum of Art, 13 years later. In the meantime, Sims finished another 13-year piece of The Recoloration Proclamation: TheAfroDixieRemixes, a 13-track album reimagining Dixie through the lens of black musical traditions such as blues, gospel, funk, hip-hop, calypso and more. Twinkle performs the opening track, but aficionados of the local scene will recognize names like Michael Mendez, Kenny Drew Jr., Geno Mays and Skunk Boogie, among others. Amid these goings-on, in 2010, Sims introduced a new project, SquareRoot of Love, named for one of his poems and presented as a dual exhibition in New York City with provocative performance artist and poet Karen Finley. An experiment in good feelings blending poetry, math, visual art, food, wine, politics and conversation, the event went well but lacked the headline punch of a black man hanging the Confederate flag and slipped by largely unnoticed.

A Strange Coincidence and Taking the Long View

Sims doesn’t mind taking his time, revisiting and retreading, reimagining and recoloring, observing year after year the minute changes in the geometry of conflict, trying to chart those chaotic orbits. Often, Sims finds his work speaking to an emerging national conversation, not because of any fire he started but because he’d been staring into those embers all along. After all, decades before STEAM was the buzzword du jour of academic administrators and marketers of every stripe, Sims was constructing a visual mathematics curriculum at Ringling College to ease the cultural tension between math and art and break down the stereotypes surrounding who’s good at math and who’s not. And he’s been hosting Pi Day events every March, combining art, math, politics and food for all who attend. But some fires burn hotter than others.

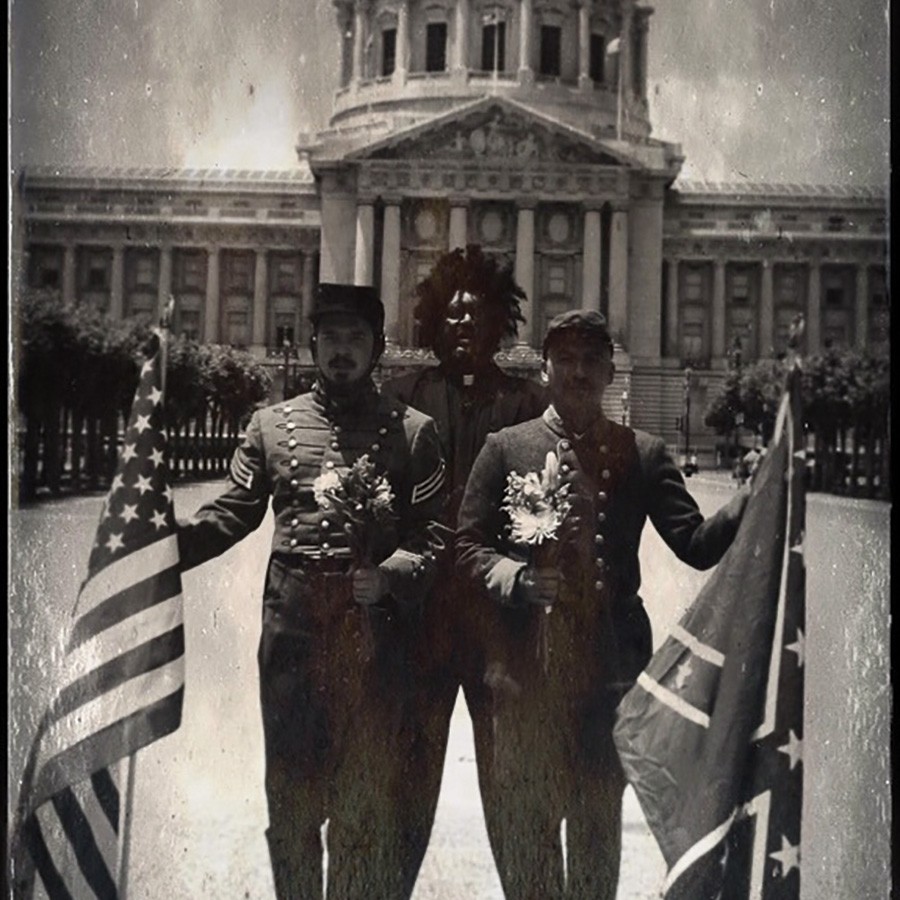

It was 2015 and the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War and Sims arranged a 13-state burial of the Confederate flag, recruiting 13 teams across the country to join together for complementary services to take place on Memorial Day, May 25. The imagery was respectful, the tone one of healing and a desire to lay old wounds to rest. Less than two months later, a neo-Confederate named Dylann Roof walked into Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and killed nine congregants, including senior pastor and state Senator Clementa C. Pinckney. By July 4 of that year, Sims had organized a response that spanned communities in all 50 states of the union—the ceremonial burning of the Confederate flag.

In the wake of the massacre, Sims began to hold these Burn and Bury events every year on Memorial Day, joined by fellow activists, artists and allies for emotionally complex proceedings steeped in anger, sadness, hope, healing and remembrance in search of resolution. “Kind of like Afro Passover,” he says. “It brings us back to the pain, so the transformative healing can move us forward.” At the same time, Sims revived the SquareRoot of Love project, breathing new life into the idea and even taking it international. The year 2017 saw Sims in a bookstore in Paris, screening films and welcoming local poets for readings, while everyone enjoyed the company and the debut of a new Bordeaux blend created in collaboration with a vineyard in Saint-Émilion, Sims’s poem printed on the label. The following year, SquareRoot of Love grew to straddle the Atlantic with dual shows in both New York City and Paris. The Paris show, scheduled for Valentine’s Day, coincided with the shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. In tribute to the victims and survivors, Sims brought the event to Sarasota in 2019 as SquareRoot of Love: Broken Heart, screening an animated video of an open letter he sent to Senator Marco Rubio, asking the Republican legislator to join calls for more gun control. 4,500 miles away in Paris, a SquareRoot of Love show full of contributors went off without a hitch

A local Sarasota TV station aired part of the video, but the fact that a local artist had created a yearly arts event that connected American artists with Parisian counterparts over a shared love of the humanities, again, went largely uncelebrated. Sims didn’t mind this either. Between the Burn and Bury memorials, the SquareRoot of Love exhibitions and his yearly Pi Day events celebrating the union of math and art and good food and good company (see a pattern?), his schedule was filling up rapidly and he was beginning to see more value in the growing number of artists and restaurateurs and community leaders on the program, the regular attendees who came year after year, than in temporary headlines and fleeting infamy.

“Part of my practice,” Sims says, “has moved into the space of creating rituals.”

The Power of Ritual and A Paradigm Shift

SquareRoot of Love in February. Pi Day in March. Burn and Bury in May. What began as disparate art projects began to look like rituals and cultural traditions, landmarks on one of the most fundamental orbits of all—the calendar. The passage of the Earth itself through space and time. Sims was no longer shocking the system with in-your-face artistic jolts but asserting systemic influence through repeated action.

“Creating periodic cycles within these chaotic landscapes,” he says, “that give a sense of identity and support to hold on to the things that we value.” Like wave amplification, each feeds the other, year after year, growing more powerful in society’s undercurrents. “That builds a rhythm,” Sims continues. “It becomes musical. It becomes a systemic part of the culture, where it seeps in in a very powerful way.”

And with this revelation comes the necessary reevaluation of prior work and priorities. It’s a paradigm shift that upends the artist’s value system and deprioritizes the created art object in deference to something more ephemeral and intangible—a lived experience that may involve visual art, poetry, food, wine, music and conversation, but transcends each individual element to amount to something more. “All the visual art stuff, all the hard-copy stuff, all the sculptures and stuff—it’s not important,” Sims says, innervated beyond his usual laconic drone. “What’s important is the ritual that comes out of it. That’s the stuff that can transmute, transform and push the culture forward.”

Not even a project Sims spent 13 years fighting for is immune from his revelation. Reflecting on the death threats he received while campaigning for The Proper Way to Hang a Confederate Flag, Sims response now belies a certain ambivalence toward that sort of artistic grandstanding disconnected from a greater immediate purpose, not grounded by ritual. “Nobody’s trying to die for some dumb shit,” he says. “The art objects, the texts, the politics all become ingredients to precipitating a certain kind of ritual that makes sense for a particular kind of community and culture. The rest is just economy.”

And so as 2020 began to unfold, Sims tended to his growing rituals. Now artist-in-residence at The Rosemary, the restaurant sponsored Sims on a trip to Italy, where he walked the streets of the OG math artist, Leonardo da Vinci, and the vineyards of Castello di Querceto, selecting a Super Tuscan to bring back to Sarasota for SquareRoot of Love: A Wine and Words Dinner in February. Hosted at The Rosemary, Sims found a seat surrounded by luminaries, as the guest list now included the likes of poet laureate Peter Meinke and civil rights pioneer Charlayne Hunter-Gault, joining Sarasota artists and leaders for a night of conversation and cuisine and collaboration. A month later, he was back at The Rosemary for American Pi: A Wine and Words Pi Day Dinner, featuring a special guest in author Stephen Ornes, an award-winning science and mathematics writer whose latest book, Math Art: Truth, Beauty, and Equations, highlighted Sims’s collection of pi-inspired quilts, created in collaboration with the Sarasota Amish community.

When the pandemic hit, there was a brief pivot and Sims penned an open letter on COVID-19 and its disproportionate effect on communities of color for The Grio and created an online video game with a Galaga feel called Korona Killa, which saw players around the world taking part in blasting COVID-19 virons and dodging bats. But come May 25, Sims was back hosting Burn and Bury 2020, joined via Zoom by countless from across the country to discuss the state of the nation and the fight against white supremacy, to share music and visual art and share in the ritual burning of the Confederate flag and come out revived, inspired and fortified to face another day.

And while Aaron Wilder, a multidisciplinary artist from Chicago, read aloud the names of 203 black men and women killed by police in 2014 and 2015, while Sims thanked him for emphasizing the importance of memorializing, a police officer was killing George Floyd, kneeling on his back for nearly nine minutes.

Sims sat down to write another letter.

A Lever to Move the World

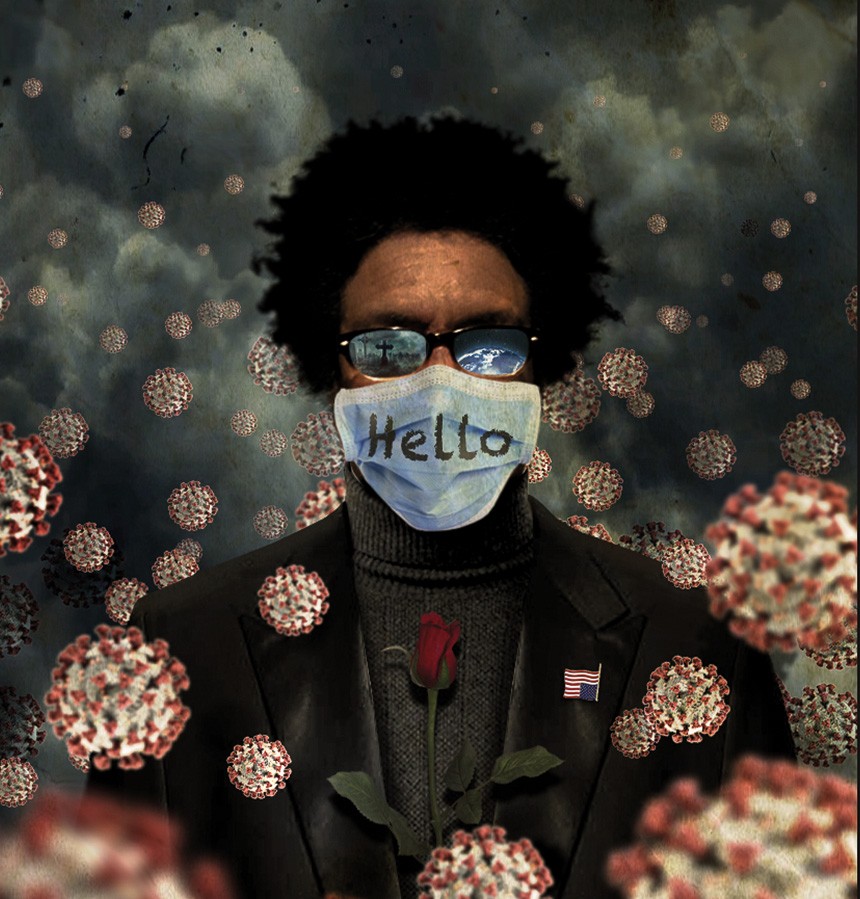

Writing letters would become a new ritual for 2020, as Sims found himself drawn to the keyboard again and again to confront his fear and vent his anger and express his hope in a year that seems the stuff of nightmares. He began painting a series of self-portraits as well, each featuring the artist outfitted in the iconic black turtleneck/leather jacket combo of the Black Panthers, an upside-down American flag on his lapel, his eyes hidden behind reflective lenses and a surgical mask hiding his nose and mouth. Sometimes he’s surrounded by giant COVID-19 virons. Sometimes the virons have police badges and flags with little blue lines drawn across them.

COVID-19. Police brutality. White supremacy. As Sims sees it, pandemics abound in 2020 America. And none of them are new, in line with Sims’s geometry of conflict. Individual expressions, such as a novel coronavirus or a particular murder, are not isolated incidents but expressions of these chaotic orbits made manifest as they engage our cultural universe.

Scientists have warned of a looming pandemic with growing urgency. Civil rights advocates have warned of police brutality for decades; anti-racist activists even longer. That individual instances cannot necessarily be predicted does not invalidate the theory, but the national reaction to the killing of George Floyd reaffirms Sims’s insistence that one person can absolutely rock the system. But only if other factors line up. “If George Floyd was killed in March, while everybody was running around looking for toilet paper, it wouldn’t have been as big,” he says. “People would have been conflicted.”

But when the orbits align, when people are stir-crazy and on edge from an unchecked pandemic, jobless on the verge of homeless as wealth and income inequality skyrockets, as racial and political tensions reach new and old heights, the killing of one man in Minnesota—a death perhaps like many others before it—can start a fire that consumes a city and a nation.

And from that destruction comes the opportunity for change. For growth. For healing.

Still, it is a violent ritual, an unwitting blood sacrifice,and Sims can’t help but hope there exists a way forward that does not necessitate death as the catalyst for change. Some other rituals people could engage in to wobble the orbits just right and bring about an amplification of love instead of violence and ride that wave forward together. Maybe that ritual involves art. Maybe it involves math. Maybe it involves good food, good company and good conversation that both brings the community together and challenges it.

“The idea of love as a food, as art, as an energy source for the soul, is so important and foundational to life and community,” Sims wrote to his attendees at this year’s SquareRoot of Love ritual. “Love, whether a verb or noun, a sugar or spice, in motion or stationary, requires many times over an expression that goes beyond the romantic to include ideas of connective attention, spiritual energy, community inclusion, and immersive conversation.”

And maybe Sims has been building such a movement this entire time, a flip side to the aggression of The Recoloration Proclamation, something built out of love, a symmetrical reflection that brings balance and context to Sims’s world.

“The SquareRoot of Love project is on the other end of all that,” he says. “Global humanity, love, food—the kind of things that bind human culture together.” He knows that the need for a simple narrative can too easily dismiss him as “the black angry artist just doing inflammatory anti-Confederate blah blah blah,” but such opportunistic tunnel vision misses the greater point. “Put into wider context,” he says, “you see that I’m working in different spaces that complement each other.”

And if the orbits haven’t quite aligned yet, that doesn’t mean they won’t. In early 2021, Sims will take the stage at the Historic Asolo Theater as the Ringling Museum of Art’s artist-in-residence, sharing the letters he wrote to the people and powers-that-be in Florida this past year, addressing issues of police brutality and white supremacy. He’ll talk about the specters of the Confederacy haunting Florida in both its statute and whitewashed monuments like the Gamble Plantation, which he reimagines as a memorial to the slaves who worked it instead of to a romanticized and revisionist way of life that never existed.

And for each, he’ll invite a representative of The System itself, such as state legislators and Chief of Police Bernadette DiPino, to deliver a response not just to Sims but to the community, hoping to engage them in those most powerful rituals of all—voting and lawmaking. “I’m using this residency to connect,” he says.

Come February it will be time for SquareRoot of Love and in March it will be time for Pi Day and in May it will be time for Burn and Bury. The old rituals are made new each year in a belief that, indeed, change is coming. But it might need a little help on its way.

So Sims will play the long game, building his Archimedean lever piece by piece, ritual by ritual, until he can move the world. SRQ